The 300 block of Park Avenue in Downtown Baltimore was at the center of several presentations by undergraduate students on Tuesday, December 6th. This block today is home to several businesses run by Ethiopian merchants, offering hair styling, meals, and other essentials. Yet this block historically has been the locus of the Chinese community in the city of Baltimore, which peaked in the 1960s.

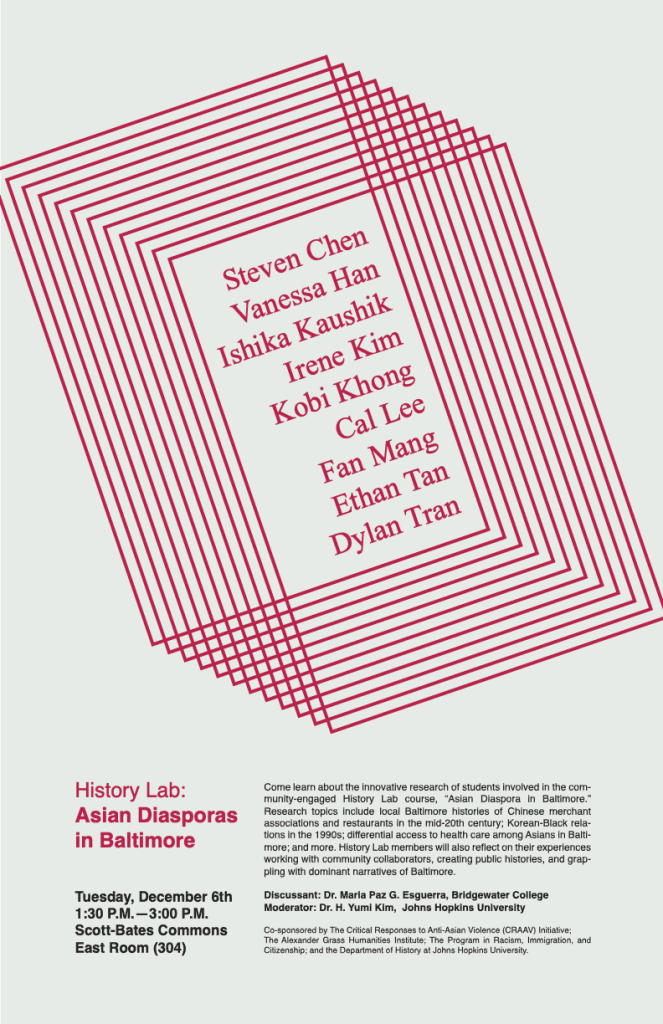

Students examined this unique block and its changes, amid the broader vicissitudes of economic and racial transformations in Baltimore, as part of their fall course History Research Lab: Asian Diaspora in Baltimore, taught by assistant professor of history H. Yumi Kim.

In March 2021, as a response to the pain and outrage among Asian and Asian-American students and others after the shootings in Atlanta, Kim, along with RIC’s Clara Han and Erin Chung, founded Critical Responses to Anti-Asian Violence (CRAAV), which has supported programming on political and cultural questions of the Asian diaspora in the United States and elsewhere. This project also helped germinate an ongoing student-led initiative to create a new major within RIC called Critical Diasporic Studies that would emphasize AAPI experiences and politics, as well as investigate global indigeneities, comparative colonialisms, and other large social questions that have been the core of the work RIC has been hosting among PhD students.

Kim’s History Research Lab course represents the meeting of CRAAV’s critical political inquiries and the student energy behind the push for new curricular offerings on the Homewood campus that better address the complex and intersecting identities of the increasingly diverse student body.

Urgent Questions

The nine students in Kim’s course faced a basic challenge: although we do know that Asian people have lived in Baltimore for over a hundred years, almost no scholarly literature documents their history. And, moreover, as the contemporary streetscape of the 300 block of Park Avenue demonstrates, this history is in danger of disappearing. The possibility of losing this history made the students’ research feel urgent.

To a crowd of around thirty other students (graduate and undergraduate), faculty, librarians and archivists, and community members, the students presented their early research findings on topics including relations between Korean and Black populations in Baltimore (Vanessa Han), local Cantonese- and Toisanese-language schools (Dylan Tran), the Baltimore Chinese merchants’ association On Leong Tong (Kobi Khong), and others. Cal Lee and Ishika Kaushik presented a draft version of a public website that will help document the Asian Diaspora in Baltimore, including the research of the students in the class.

The event was co-sponsored by CRAAV, the Alexander Grass Humanities Institute, the Department of History, and RIC. Maria Paz G. Esguerra, assistant professor of history at Bridgewater College, provided comments on the presentations.

Community-based Learning

Throughout the fall semester, Kim’s class hosted local community leaders. Students reported that speaking with these figures, including longtime Baltimore residents Rockwood Lee, Vincent Liu, and George Yung, changed the way they understood the history of Asian people in Baltimore. Their accounts of growing up and living in the city did not always conform to what the students found in the secondary literature about other locations in the United States. Students further pointed out that some of the conceptual vocabularies that scholars tend to use did not seem adequate to the granular details of these individuals’ biographies, which, one student said, “brings the content of the course to life and makes students feel so much more connected to and passionate about the issues we’re learning about.”

An engaging course can be life-changing as well as educational

Tobie Meyer-Fong, Chair, JHU History

Wrestling with the contradictions and disagreements among historical actors and interviewees, locating archival records, and finding the most appropriate analytic frameworks were some of the challenges the students faced. Students grappled with difficult interpretive questions, and Kim encouraged them to derive differing interpretations to questions like: Does the succession of Chinese-American businesses by Ethiopian-American businesses on Park Avenue represent what scholars call “overlapping diasporas” or is it better understood as “gentrification”?

In addition to conducting oral interviews, the students accessed archival collections held by the National Archives and Records Administration, the University of Baltimore, the Library of Congress, the Maryland Center for History and Culture, and others.

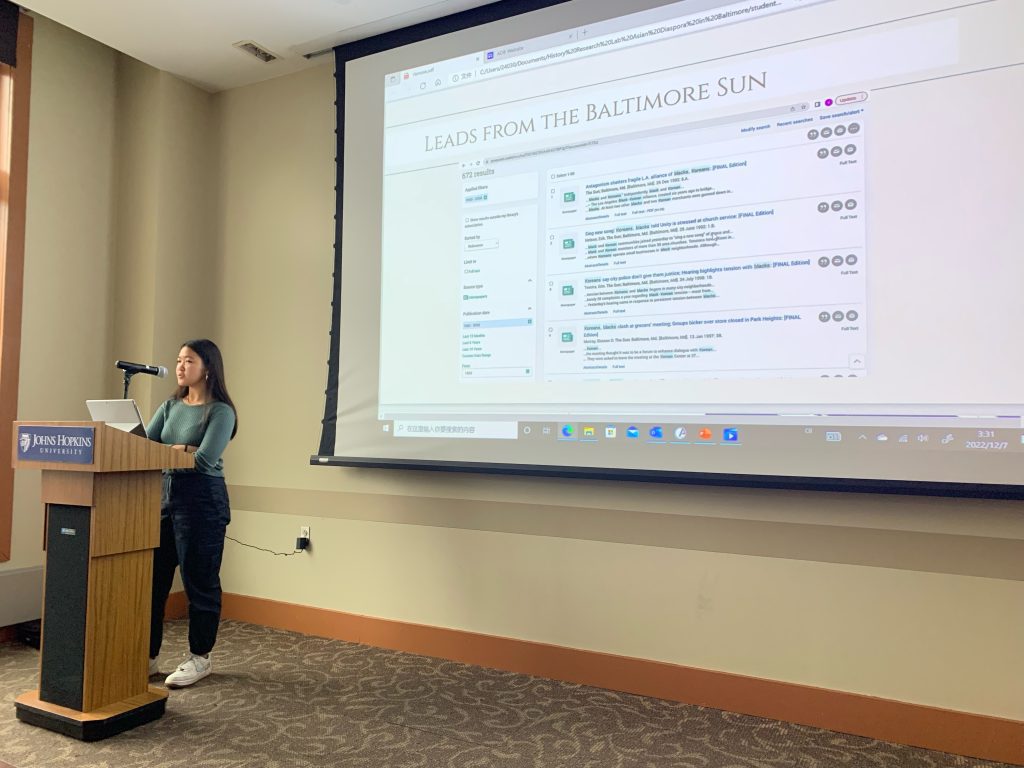

Combing old articles in Baltimore newspapers, including the Afro and the Sun, also proved fruitful. But this approach raised a question that vexes all historians using full-text search capabilities today: how to search the archives for categories we use today that may not have been in use, or used in familiar ways, in the past? Even if students were interested in relationships and solidarities among different Asian populations in Baltimore, they nevertheless were limited by terms like “Chinese” or “Korean,” which may have made these group seem more separate than interlinked.

Know History, Know Self

Informed by the Center for Social Concern’s community-based learning initiative, Kim’s History Research Lab is one of a set of similar new courses devoted to giving students experience with original research in primary sources, no matter what their major may be. Tobie Meyer-Fong, chair of the Department of History, reflected on the “powerful reminder” that the presentations offered: “an engaging course can be life-changing as well as educational. The creativity and energy of the professor and students was on full display as they summarized their findings. I found their pride in their work and humility in relation to their community interlocutors inspiring, as was the fact that so many of them seem intent on pursuing the lingering questions that could not be answered within the limiting framework of a single semester.” Meyer-Fong said she was “awed” by Kim’s efforts and excited by the possibilities for additional courses like this one.

Within the student-proposed Critical Diasporic Studies major, there would be room for analogous courses on not only the Asian Diaspora in Baltimore, but also the Latinx and Indigenous experiences, as well as other histories that connect local and global, excavating otherwise forgotten and overlooked aspects of Baltimore’s relationship to the world and its multilayered past.

First-year student Vanessa Han told RIC that Kim’s History Research Lab has cemented her belief that majoring in history, which she has hoped to do since working on civic campaigns with GirlGov in high school, is the right decision for her.

Han explained that conducting original research is both challenging and rewarding. “Even after I had collected all these primary sources,” she noted, “I was stuck on how I would even begin to summarize what I had found into a single argument. Ultimately, through various discussions with the class and Professor Kim, it became easier to let my research guide me to a question.” In this way, her investigation did not impose a predetermined framework, but instead she allowed the analysis to emerge organically from the primary sources.

This History Research Lab offered a supportive environment for students to explore and institute the mantra shaping Catherine Choy’s Asian-American Histories of the United States: “No history, no self. Know history, know self.”

Despite the “lab” in its title, the course violated laboratory conditions in the best way, by allowing students to produce knowledge in conversation with the outside world, rather than being sealed off from it. If Baltimore is now at slightly less risk of forgetting its Asian heritage, it will be because of the work Kim and her students have completed.

Photos by H. Yumi Kim, Wesley Sampias, & Stuart Schrader