by Sheharyar Imran

In the wake of the 2020 uprisings against the persistence of police brutality, anti-blackness, and the uptick in anti-Asian violence across the world, undergraduate students at Johns Hopkins University voiced a vociferous and collective demand: the creation of an academic program that foregrounds questions of white supremacy and racial violence in the United States and beyond, with a particular emphasis on Asian, Black, and Indigenous concerns. These efforts have culminated the formation of the Critical Diasporic Studies (CDS) working group, composed of undergraduates from across JHU as well as faculty members and graduate students affiliated with the Program in Racism, Immigration, and Citizenship (RIC).

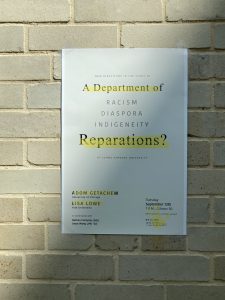

In May 2022, the RIC faculty board voted unanimously to support the proposal for a new undergraduate major, tentatively called Critical Diasporic Studies. On Tuesday, September 13, 2022, RIC hosted a roundtable event titled “A Department of Reparations?” to further echo student demands for new curricular initiatives at JHU. Featuring eminent scholars in the fields of racial and ethnic politics and transnational cultural studies, Dr. Adom Getachew (Chicago) and Dr. Lisa Lowe (Yale), the roundtable sketched the contours of what new directions in the study of racism, diaspora, and indigeneity might look like in our present moment.

This invigorating discussion focused on how new intellectual approaches to understanding and producing knowledge about racial politics must transcend previously entrenched frameworks in the social sciences and humanities—most of which tend to focus heavily on singular and discrete identity categories and region-specific concerns, growing out of Cold War–era area studies—while also creating meaningful relations with local, often underserved, communities in which elite universities are situated. Dr. Stuart Schrader, associate director of RIC, moderated the roundtable, which also included Dr. Nathan Connolly, director of RIC and Herbert Baxter Adams Associate Professor in the Department of History, and Joyce Wang, JHU ’22 and member of the CDS working group. The room was filled, with an audience of ninety undergraduates, graduate students, faculty, staff, and administrators. RIC provided free copies of the most recent books by Getachew and Lowe to students who attended.

Both Getachew and Lowe have been instrumental in establishing new academic programs committed to racial justice at the University of Chicago and Tufts University, respectively. The Department of Race, Diaspora, and Indigeneity was founded at University of Chicago in Spring 2022. The founding of the department was the outcome of student and faculty organizing that began in Fall 2020 but built on more than a decade of discussion and debate. At Tufts University, the Consortium of Studies in Race, Colonialism, and Diaspora (RCD) officially departmentalized in 2019, and through a $1.5 million grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation was able to hire new, specialized faculty members, with a commitment to renewing the curriculum and diversifying the faculty at the university.

Now Samuel Knight Professor of American Studies and Professor of Ethnicity, Race, & Migration at Yale University, Lowe stressed that new efforts for the study of racism and anti-racism must necessarily be comparative, transnational, and relational in their outlook, or else they preclude a fuller understanding of the nuances of racial politics across the world. Black freedom in the United States, she argued, has always been intricately connected with anti-colonialism in India and other parts of Asia. Citing W. E. B. Du Bois’s Black Reconstruction, she argued that the overthrow of slavery and resistance to finance capitalism in the Americas always hinged on transnational solidarity. These efforts combined the intellectual and political projects of oppressed peoples from the world over, none of whom was identical, yet whose histories and fates shared important connections, highlighting the necessity of a global framework for anti-racist thinking. “Our different histories are so linked. But I think in this particular moment, it’s so hard to see that because the racisms are so exacerbated, so targeted. It’s very hard to move out of our individual positionalities and see those links,” she said. Hence, new curricular efforts “should answer to such questions as: What is the specificity of racial capitalism at this moment? Why is it taking the form of enhanced carcerality? Why does carcerality build on the history of slavery?”

The roundtable discussion emphasized the point that while broadening our intellectual questions and frameworks is essential to understanding the current moment in which we’re living, such a project is not purely an intellectual one. Connolly stressed that community partnerships must be a key part of any new curricular agenda if we seek to understand and respond to the imperative of anti-racism today. Invoking the historical, albeit racist, commitment of JHU faculty to conceive of academic scholarship as inextricable from civic engagement, Connolly argued that new efforts in the social sciences and humanities must heed historical inheritances while necessarily challenging and transcending their racialized underpinnings. Intellectual programs that investigate the social and political dynamics of the present cannot be confined to the classroom. They must also include a practical engagement with local communities as sites of knowledge production, lived commitment to racial justice and, above all, reparative resource allocation.

Dr. Christy Thornton, Assistant Professor of Sociology and Latin American Studies, who attended the roundtable, noted that JHU undergraduates have been seeking greater coverage of Latinx immigration to the United States in courses in the social sciences. “We see the push for new curricular offerings in diaspora and indigeneity, which Joyce Wang outlined, as complementary to our work to expand coverage in Latin American, Caribbean, and Latinx Studies. This would be a very welcome development from the point of view of our program.”

Getachew, Neubauer Family Assistant Professor of Political Science and the College at the University of Chicago, further stressed the importance of staying true to both the intellectual and political agendas guiding the creation of such initiatives, highlighting the limits of departmentalization without a broader political focus. “I don’t think you should expect departments or the creation of academic programs to do all the work. There are things that departments can accomplish, and there are others they cannot,” she said, noting that developing broad constituencies is crucial to transformative change. At Chicago, the “More Than Diversity” faculty initiative, which aided in the development of the Department of Race, Diaspora, and Indigeneity, demands not only curricular changes and the hiring of new faculty. It also calls for the creation of a Truth and Justice Commission to study the university’s relationship to the south side of Chicago, as well as a demand to disband the University of Chicago Police Department. These issues typically fall outside the ambit of departmental concerns, so it’s important for emerging initiatives to think beyond narrowly defined academic projects. Instead, Getachew stressed, they should pursue both intellectual and political projects simultaneously, without losing sight of either.

Rachel Fink ’24 (International Studies) found the discussion helpful in thinking about the key role played by universities in perpetuating and responding to racial discrimination. “I really enjoyed this event, in part because it was an open space to express nuanced and deeply founded criticisms of institutions which have historically invested in and reproduced racism and colonialism within their own cities and academic contributions. Yet, it also offered ideas and firsthand experiences of pushing these institutions towards progress and using their resources and status to uplift systemically underrepresented students and academics,” Fink said.

It remains to be seen what a Department of Reparations could possibly look like. What this stimulating roundtable made clear is that universities need to be radically reimagined. The already lofty task of education needs to be woven together with the goal of justice, embodied in a commitment to repair historical and institutional wrongs—inside and outside the classroom.