About fifty commemorators convened in a prayerful mood in the courtyard of the Carroll Mansion on the Homewood Campus of Johns Hopkins University in the early afternoon of January 22, 2022. The reflective group was bundled in heavy jackets against the sharp cold. The purpose was a formal “Ritual of Remembrance: A Musical Celebration Honoring Homewood’s Black Ancestors.” Scores of people of African descent were enslaved on the school’s grounds in the early 1800s. Charles Carroll Junior, the son of Declaration of Independence signer Charles Carroll of Carrolltown, owned the five-part brick Federal style house and its 140 acre farm.

Shawntay Stocks, the administrator of Inheritance Baltimore, a new collective of Hopkins professors, researchers, archivists, and staff which won funding from the Mellon Foundation in 2020, opened the event and signaled the drummer Menes Yahuda, the founder of the local musical group Urban Foli, to strike the bell and drum, initiating the proceedings. Inheritance Baltimore consists of the Billie Holiday Project for Liberation Arts, an intellectual hub for Black Baltimore archival preservation and exhibition, and the Race, Immigration and Citizenship Center in the Krieger School. The Homewood Museum also sponsored the event.

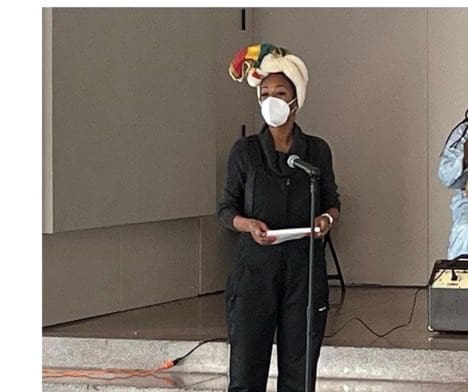

The tone then shifted from somber reflection to joyful celebration, and lead by Jackson and research professor Kali-Ahset Amen, the cortege began a march across the campus grounds to the Levering Hall Glass Pavilion, attracting curious students as it wound its way. There, Amen, who is co-director with Jackson of the Billie Holiday Project, introduced the hour-long program designed by IB postdoctoral fellow Jasmine Blank Jones, who wore a bright red long sleeved shirt bearing the motto: “Ritual of Remembrance.” Blanks Jones greeted the crowd and turned the program over to the lead dancer of the Foli musical collective, world-wide-known Amaniyea Tayne.

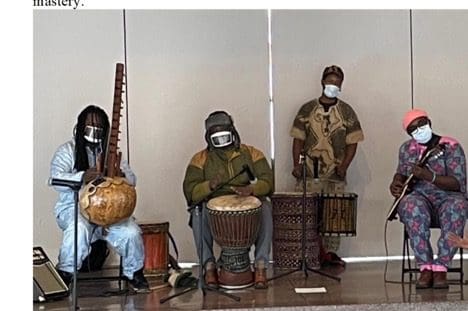

For about fifteen minutes, lead dancer Sister Amaniyea regaled the audience, seated in chairs at the pavilion main floor, while acoustic guitarist Diandre Dukes, Menses on the djembe, Yuma Vellome on the Dundun, and Amadou Kouyate on the most ancient Malian empire instrument–the many-stringed, gourd body Kora–serenaded on the stage behind her. Wearing a two-piece boubou dyed with light blue and purple Adinkra patterns, she opened with a salvo of stirring invectives, challenging the audience to accept inspiration and guidance from the vital act of remembrance. She insisted upon the fundamental, transformative value in recovering the lives of the enslaved. “The time is here! It’s now and shall be forevermore! Pay attention!” After issuing the call and eliciting the response, Tayne then turned to traditional rhythmic dances of lunges and swift steps, often pantomiming winged flight with delicate, rhythmic mastery.

Blank Jones, who earned a doctorate in both Africana Studies and education at the University of Pennsylvania, is also a board member of the Urban Foli arts collective. She created a moving choreopoem recovering the voice of Charity Castle, a Black woman enslaved by Charles Carroll Jr. in 1814 and who endured his repeated sexual assault. Her poem emphasizes the thankful joy of the enslaved, resuscitated to witness the sight of their black descendants on the Homewood grounds. It was read and performed by Center for Africana Studies major Yasmine A. Bolden, a lithe and dynamic Hopkins undergraduate student. Crying out to the audience, “It feels good to be seen!,” Bolden swept from celebration to lament, signaling the self-endowed black rites and temporality in funereal touches, “…the year I lost the baby.” Here she delivered the punch of Blanks Jones work and its efforts to formally invoke and memorialize Black people whose lives slipped outside of formal antebellum era records. Often the children of the enslaved died before either being formally christened or reaching an age to have been recorded by name in the ledgers kept by property owners.

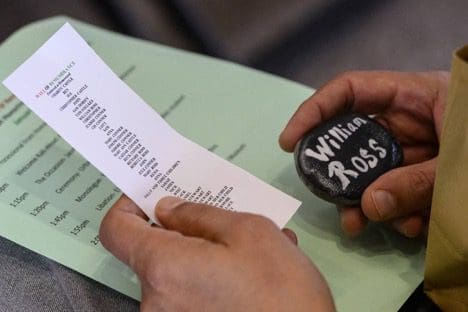

As Bolden crescendoed to a climax, the Ritual of Remembrance team members distributed memory bags to the audience, containing a nametag made of stone for a person enslaved on the campus, such as John Castle. On the early 19th century Carroll farm lived several large Black families, the Conners, Castles, Buckmores, Stewarts, and Rosses. Team members then lead the audience in a ritual to call out loud the names of 38 people, who had not been invoked on the campus in two centuries. Then the Urban Foli mistress of ceremony invited the Homewood audience to the front for a group dance, a portion of the ceremony braved by about fifteen intrepid and skilled women, who savored the mounting frenzy of the musicians.

IB team members Jeneanne Collins, a storyteller and folklorist, and Elder-in-Residence Charles Dugger, a longtime Baltimore City school teacher and activist, concluded the program, followed by a recessional.