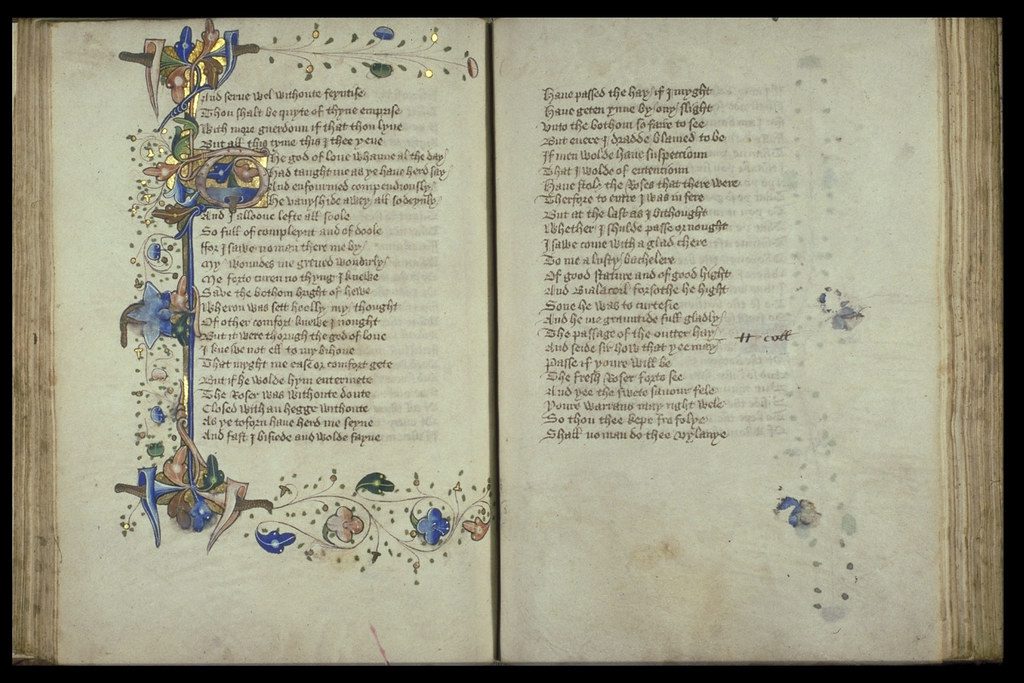

(border decoration from The Romaunt of the Rose England: c.1440-1450 University of Glasgow Library, MS Hunter 409 (V.3.7))

Introduction

Chaucer’s life circumstances and language gifts contributed much to the development of the English language, and he is often credited with ‘founding’ or ‘inventing’ English literary language and, sometimes even, English as we know it. The expansion of the vocabulary of English did not, however, begin with his writings. In Old English, an extensive vocabulary was referred to as a “treasure box” or a “word hoard” to be unlocked in speech, and Norse words and many derived from Latin were added to that store. That hoard included rich resources for creating new words out of old ones (prefixes and suffixes to add to existing words, and an inclination toward compounding — as in modern day German) whereby English vocabulary was continually enlarged by its own means, and, also, a store of words derived from Old Norse (as a result of Viking invasions and conquests between (roughly) 780 – 850. The watershed for Chaucer’s Middle English was the Norman Conquest in 1066, when the existing English language was quickly permeated by that of the French invaders, who immediately became its ruling class. The French brought with them social customs that became associated with ideal social behaviors, and the French words and phrases that entered English were believed to refine rougher English forms. This process was well under way by the latter half of the fourteenth century when Chaucer began to write. Latin words had continued to enter the language (though at a lesser rate) in the same period. Of equal importance, however, was an ongoing antiquation of certain words and expressions. Chaucer embraced every aspect of this linguistic evolution. Chaucer coined words from English roots and suffixes, and borrowed new words from French and Latin in great numbers. He also seems to have tired of new vocabulary quickly and so continually coined or borrowed new words over the course of his career while words he had coined or borrowed (or, in many cases, simply used) before, fall out of his active vocabulary.

Chaucer, who inhabited the court, dabbled in legal work, and travelled throughout western Europe, would naturally (and necessarily) have spoken and written French and Latin and clearly learned Italian well later in life. It would be inaccurate to say, however, that Chaucer’s audience would have perceived hard distinctions between the words derived from these languages. Chaucer was equally alert to the demands of writing literary works in English, since this had rarely been done after the Norman Conquest with serious ambition (with the idea that English works could be the equal of poetry and prose in Latin and French in particular).

Chaucer’s vocabulary is thus built on a dynamic network of origins leading to an equally dynamic set of associations with other vocabularies and linguistic history (newer borrowings might be heard more readily as such over against borrowing that were, say, embedded in the language prior to the Conquest).

Following are just a few Germanic words that were naturalized in Chaucer’s London:

- algates (nevertheless)

- ay (always, ever)

- brennen (to burn)

- bresten (to burst, break)

- casten (to throw, utter)

- deyen (to die)

- rennen (to run)

And here are some that that you will recognize from Modern English: both, callen, felawe, fro, geten, knyf, lawe, lowe, same, wing, wrong, wyndowe, they, though, til, dwellen.

Following are some words drawn from French: curteis, debonair, gentil, noble.

A few Old Norse words include egg, husband, window, take, leg.