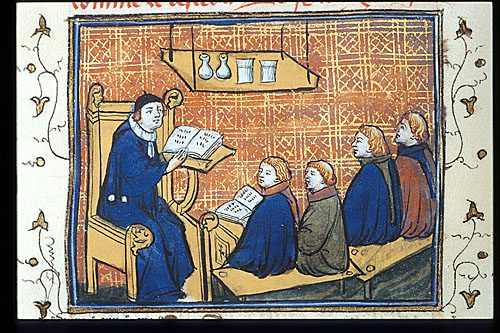

(detail of miniature from British Library, Royal 17 E III, f. 36)

Introduction

There are a variety of very good editions of Chaucer in print, each with useful introductory material about the language of Chaucer’s day, its grammar, and its rules of syntax (especially as they differ from our own).

The Penguin editions of Chaucer’s major works are careful and scholarly but also ideal for students:

- Geoffrey Chaucer. The Canterbury Tales. ed. Jill Mann. London: Penguin, 2005.

- Geoffrey Chaucer. Troilus & Criseyde. ed. Barry Windeatt. London: Penguin, 2003.

The Oxford Chaucer (eds. Christopher Cannon and James Simpson, Oxford: OUP, forthcoming, March 2024) contains all of Chaucer’s known works, and provides a great deal of introductory material for a reader coming to Chaucer for the first time, as well as careful glossing of difficult vocabulary on each page.

Of the translations of Chaucer available in print and online, many are accurate; some are deft and elegant. But Chaucer’s Middle English is close enough to our own language that it is worth taking the time to learn the basics so you can read his poems in the original. The greatest challenge is learning to recognize a small number of frequently used words and spellings that were not yet standardized in the forms we know them. Chaucer’s poetry often depends on the conventions of Middle English for its effects, not only in the experience of its unique rhythms, but for its meanings. Underneath every line of Chaucer is a subtle wit, inherent to his affection for (and dexterity with) the double meaning. Translation inevitably deadens much of this friction, and, with it, the kinds of enjoyment to be had from taking in all of Chaucer’s wisdom.

There is also no better way to get a general sense of the nature and melodiousness of Chaucer’s verse than by listening to scholars read it aloud. You can follow along as you listen to recordings of Larry Benson and Helen Cooper reading aloud on the next pages.